From the grasslands of the Serengeti to Great Barrier Reef seagrass meadows, new research shows elephants and turtles can use similar grazing strategies.

In my first PhD chapter which has just been published, we found that green turtles can graze on seagrass meadows in the Great Barrier Reef in a similar way to their terrestrial herbivore counterparts. For decades ecologists have had an in depth understanding of how grazers feed on grasslands, but we are only just beginning to understand the impacts of grazing in the large underwater meadows of the Great Barrier Reef.

Green turtle grazing in seagrass meadow (Abbi Scott)

We carried out new research into green turtle grazing in the seagrass meadows around Green Island off the coast of Cairns. By using exclusion cages that prevent large grazers such as turtles and dugong from grazing on small areas of seagrass, and comparing these to the naturally grazed meadow, we were able to understand the impact of grazing in the seagrass meadow here. This new study has uncovered for the first time some of the novel feeding behaviours by green turtles at Green Island, these are similar to grazing behaviours of herbivores on land, and by green turtles in other locations but have never been documented before in the Great Barrier Reef.

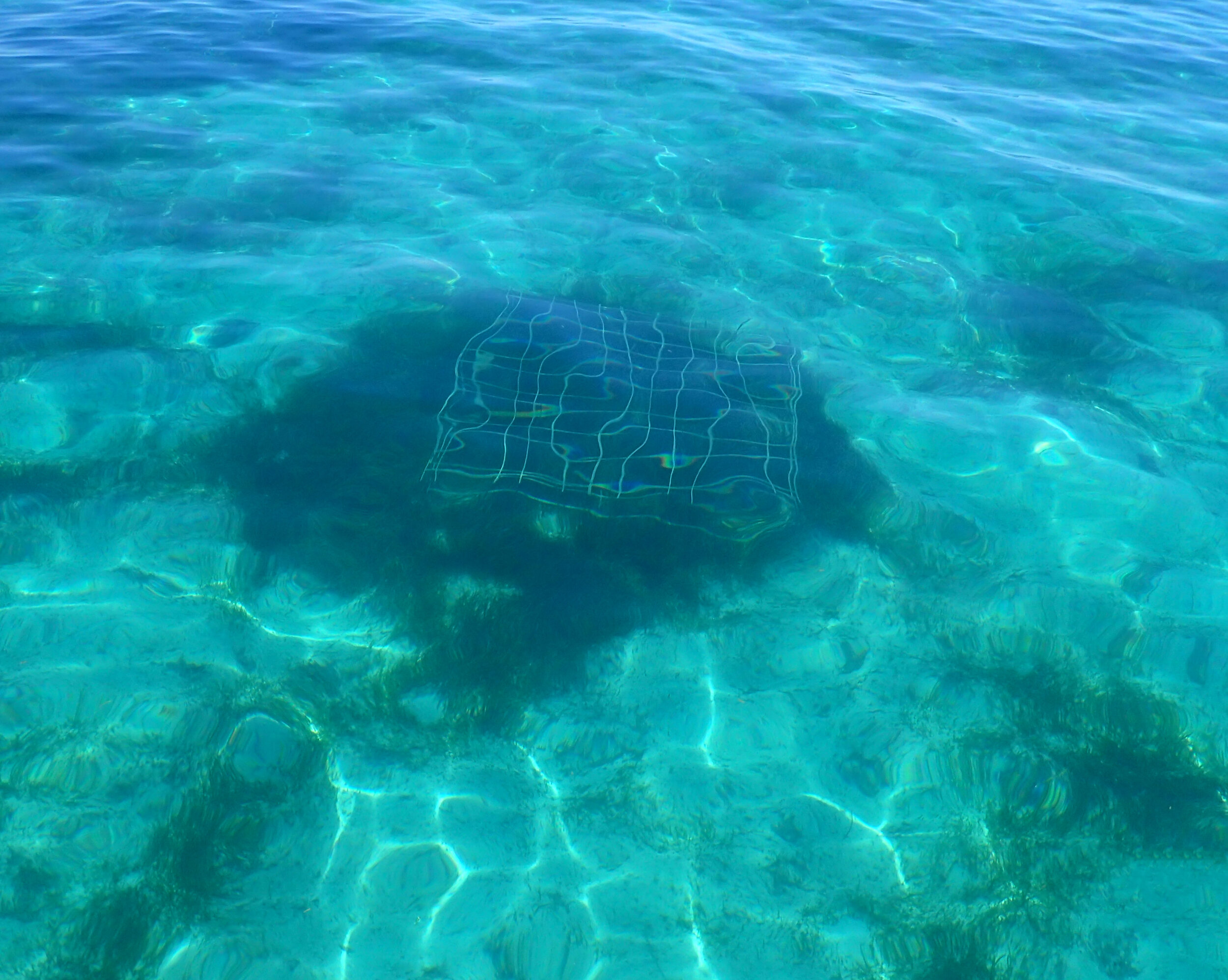

Exclusion cage in the Green Island seagrass meadow (Abbi Scott)

After two months with exclusion cages placed in the seagrass meadow at Green Island, we noticed a sudden loss of seagrass in one small patch while the rest of the meadow remained untouched. Camera footage revealed that this seagrass loss was due to green turtles feeding intensively in this small patch, green turtles were seen grazing around the exclusion cages and caused a 60% reduction of seagrass compared to caged plots within the grazed patch. In a very rare observation only documented once before, green turtles were seen feeding on the belowground roots and rhizomes of the seagrass in the grazed patch. While this grazing caused large losses of seagrass within the small grazed patch, the rest of the seagrass meadow remained long and lush. See photos below of the cages inside this grazed patch.

In seagrass meadows in other parts of the world, and on land, grazers will target nutrient rich areas of grasslands, feast on small patches of grass and graze then on the nutrient rich regrowth. We think that this grazing behaviour at Green Island could also be motivated by nutritional requirements, perhaps targeting higher nutrient levels in the seagrass blades but also allowing them to dig down and feed on the high carbohydrate roots and rhizomes. Green turtles can maintain these grazed patches for a few months and move between them, but more research will show whether this is a repeated behaviour at Green Island.

Even though there are large areas of seagrass in the Great Barrier Reef and large populations of green turtles, this is the first time that scientists are uncovering more about the feeding behaviour of green turtles within seagrass meadows here. This new work will help us understand more about the seagrass grazer system as a whole, and could help inform measures to conserve both the seagrass meadows in the Great Barrier Reef and the green turtle populations that rely on them.

Graphical abstract summarising the findings of my new paper.

If you want to listen to me chatting about this research, you can catch up with my interview on ABC Far North Queensland radio with Phil Staley here or below: https://www.abc.net.au/radio/farnorth/programs/mornings/turtles-are-fussy-eaters/12817598

And you can read the paper in full here: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2020.105183